The Regional President arrives in Tokyo with a proven track record. His tenure in Seoul was defined by high-velocity pivots and a 40% growth spike achieved through direct, top-down mandates. In the Tokyo boardroom, he applies the same logic. He issues a clear directive for a mid-quarter resource shift. The Japanese leadership team nods in unison. They offer no counter-arguments. They smile.

Six weeks later, the shift has not occurred. Budget lines remain frozen. The “alignment” perceived in the meeting was a phantom. The President interprets this as a lack of urgency or passive resistance. He doubles down on the directness that yielded results in Seoul, unaware that his presence is actually deepening the organizational paralysis.

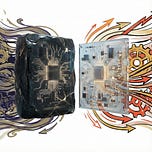

This friction is the result of a fundamental diagnostic error. One of our team members, having operated extensively in both Japan and Korea, summarized the reality: “Japan and Korea look similar from the outside. Inside, they operate on completely different systems.” The executive is attempting to run high-performance software on a hardware architecture that does not recognize the code. The fluency gained in Seoul is not just non-transferable; it is currently a liability.

The Mechanism: Proximate Operating Model Mismatch

This is not a culture issue. This is a Proximate Operating Model Mismatch.

Global executives frequently group Japan and Korea into a single “East Asia” bucket, assuming that shared Confucian roots translate into identical levers of corporate power. This is a failure to recognize the divergent logic of authority and risk ownership. In the Korean corporate system largely defined by the chaebol architecture, authority is a visible, vertical spike. It is declarative. The “owner” of a decision is identifiable, which allows for rapid pivots because risk is concentrated at the top.

In the Japanese system, authority is a distributed, horizontal web. It is implicit.

When an executive applies the Korean “Direct Instruction” model in Japan, they are not motivating the team; they are short-circuiting local risk-management protocols. In Japan, the “Room” decides, not the individual. The mechanism of kuuki o yomu (reading the air) is not a social nuance; it is a sophisticated data-gathering process used to ensure that no single individual carries terminal liability for a failure.

Real-World Proof: The Reliability vs. Urgency Divide

The functional difference is best observed in the operational logic of market leaders like Samsung and Toyota.

Korea (Urgency Logic): The system is built for speed, fueled by visible ambition and the pressure of rapid response. Success is measured by the ability to seize a window of opportunity before it closes.

Japan (Reliability Logic): The system is built for stability and absolute risk prevention. Success is measured by the total elimination of variance.

When a global lead demands “Korean speed” within a “Japanese reliability” architecture, the result is Systemic Friction. The Japanese organization instinctively slows down to verify the foundation the executive is trying to bypass. This creates a “Silent Failure”: momentum dies in the invisible layers of middle management because the “Direct Instruction” has bypassed the necessary internal consensus-building (nemawashi) required for a Japanese team to feel safe moving forward.

The Strategic Shift: From Speed to Structural Integrity

The shift requires moving away from the belief that “localization” is about communication style. It is about recognizing that the Japanese market does not value the “Pivot”; it values the Immutable Plan.

In Korea, changing direction mid-stream is viewed as agility. In Japan, changing direction is viewed as a failure of original governance. If the plan changes, the consensus that thousands of man-hours built is invalidated. You have effectively reset the “Trust Clock” to zero.

The Single Irreversible Insight

In Japan, alignment is not an agreement on a goal; it is a collective insurance policy against public liability.

Until an organization understands that its Japanese deputies are more concerned with the permanence of failure than the velocity of success, strategic initiatives will continue to stall. In Western and Korean models, failure is often a data point for iteration. In Japan, public failure is an institutional mark that affects shin’yō (trust/credit) for decades. The caution observed is not hesitation; it is the disciplined defense of institutional trust.

Explicit Reframing: Risk Architecture

It is not “Indirect Communication”. It is a Distributed Responsibility Protocol. The ambiguity encountered in meetings is a structural safeguard designed to keep options open until absolute certainty is reached.

It is not “Slow Execution”. It is Pre-emptive Risk Mitigation. The time spent in “unnecessary” meetings is the time required to build the structural spine that ensures the project will not fail once launched.

This explains why Japan maintains dominance in sectors where error is catastrophic, precision robotics, high-speed rail, and advanced materials while struggling in fast-moving software-as-a-service (SaaS) environments. The “Operating System” is hard-coded for a world where errors have terminal costs. When you treat the Tokyo office as a “less efficient” version of the Seoul office, you signal that you do not understand the stakes. You become the “Risk” that the local system must manage and eventually isolate.

The Bottom Line

Success in proximate markets like Korea creates a false sense of competency that leads to strategic drift in Japan. You are looking for vertical authority in a market that functions through horizontal consensus, mistaking the silence of a risk-averse system for the compliance of a high-speed one. Until the Japanese mechanism is secured rather than accelerated, directives will continue to dissipate without execution.

Over to You

In your last three strategic pivots in Japan, did the “alignment” you received in the boardroom result in immediate resource movement, or was it merely the “Air” adjusting to your presence?