The Global CMO clicks through the final slide of the “Vision 2027” deck. It is a masterpiece of modern corporate communication: five slides, high-resolution lifestyle photography, three bold pillars, and a single, soaring call to action. The room in Tokyo is silent. The Japanese Managing Director nods once, eyes fixed on the empty space at the bottom of the screen. To the CMO, this silence is the quiet weight of alignment. To the local team, it is the sound of a structural void.

Two weeks later, the initiative has not moved. There is no budget allocation, no agency brief, and no internal mobilization. When the CMO follows up, the local team asks for a “clarification meeting.” They request the raw data behind the third pillar. They ask for the specific historical variance in the Kansai region from 2019. They ask for a slide-by-slide breakdown of the risk mitigation strategy for a hypothetical supply chain shift that wasn’t even mentioned in the deck.

The CMO views this as “stalling” or “lack of strategic thinking.” The Japanese team views the CMO’s deck as “irresponsible” or “empty.” Both are high-performing professionals. Both are operating with perfect internal logic. Yet, the brand is now bleeding time, and the executive’s credibility is eroding because the tool designed to create momentum, the presentation has instead functioned as a brake.

The Documentation-as-Governance Trap

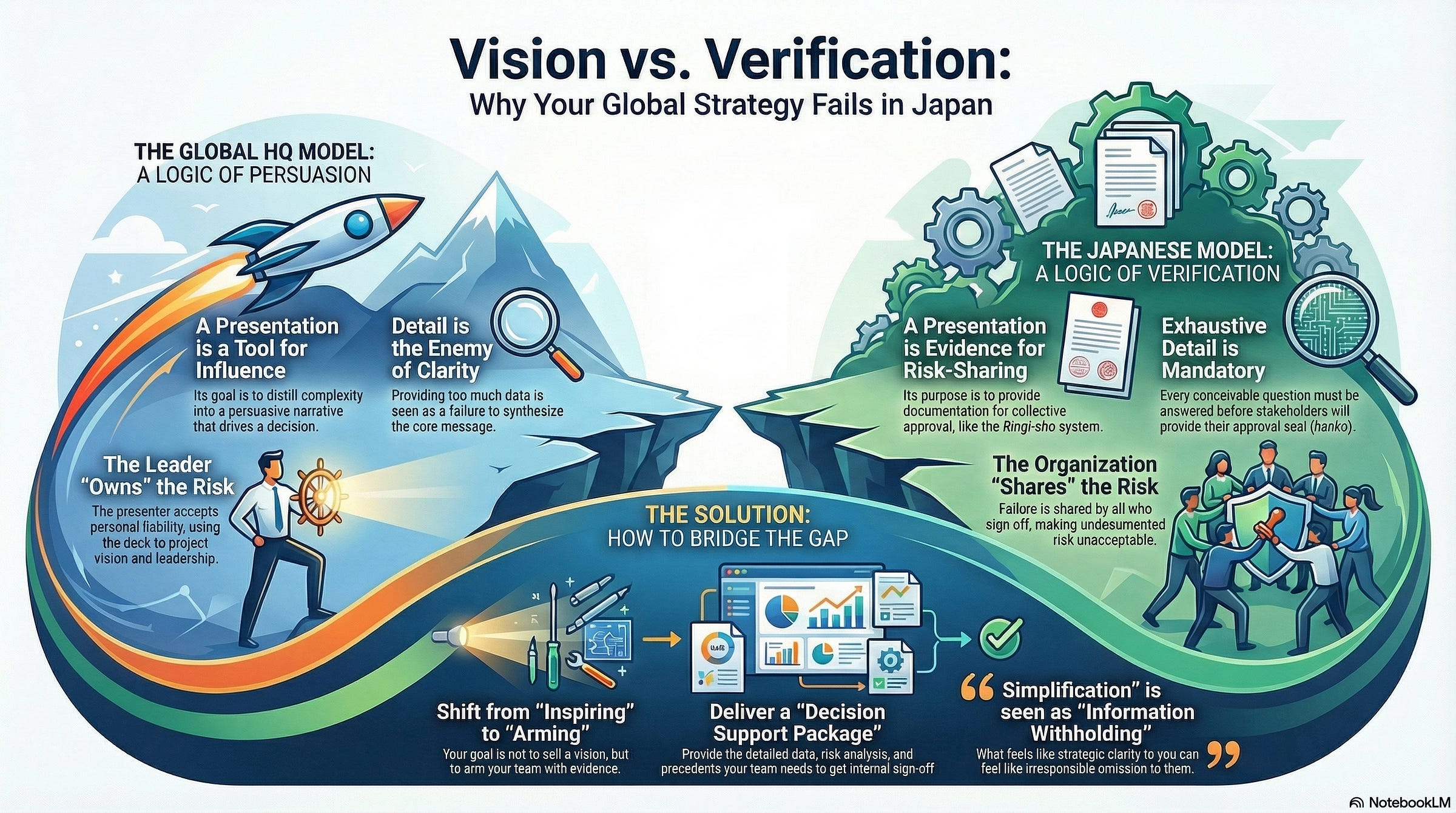

This is not a culture issue. This is an Operating Model Mismatch. In most global headquarters, a presentation is an instrument of influence. Its success is measured by its ability to distill complexity into a persuasive narrative that drives a decision. The presenter is expected to “own” the strategy, and the slides are merely a backdrop for their leadership. In this system, detail is the enemy of clarity. If you provide too much data, you have failed to synthesize the problem.

In the Japanese corporate system, the mechanism is inverted. A presentation is not a vehicle for persuasion; it is a tool for structural insulation.

Consider the Ringi-sho, the traditional Japanese system of circulating a document for formal approval. This process requires every relevant department to affix their seal (hanko) to a proposal before it reaches the top. This is not just a signature; it is a transfer of collective liability. If a project fails, the failure is shared by everyone who signed off. Therefore, no one signs until every conceivable question has been answered and every risk has been documented.

A presentation in Japan is effectively the visual executive summary of a Ringi-sho. Its purpose is to provide the evidence necessary for a manager to safely distribute risk across the organization. When a global executive presents a “clean,” narrative-driven deck, they are asking their Japanese counterparts to accept 100% of the risk without providing 100% of the documentation.

This behavior is visible in the structural rigor of companies like Toyota or Panasonic. Within these organizations, the “A3 report”, a single sheet of paper containing the background, current situation, root cause analysis, and proposed countermeasure is the gold standard. It is not designed to be “pretty.” It is designed to be exhaustive within a fixed boundary. If a global leader presents a deck that ignores the “root cause analysis” or the “historical background,” they are not seen as a visionary leader; they are seen as a person who has not done their homework. The resulting paralysis is the system’s natural immune response to undocumented risk.

The Evidence-Based Permission Architecture

To move a brand forward in Japan, the leadership must undergo a strategic shift in how they define “clarity.”

The Irreversible Insight: In Japan, a presentation is not a catalyst for a decision; it is the physical evidence that a decision has already been safely negotiated.

This shift requires moving from a logic of Persuasion to a logic of Verification. In a Persuasion-based model, you win by narrowing the focus to the most compelling “why.” In a Verification-based model, you win by widening the scope to include the most exhaustive “how” and “what if.”

This problem is not about “localization” of language. It is about the design of operating authority. When a global HQ sends a deck to Japan, they believe they are providing “direction.” In reality, they are providing a “permission structure” that is too weak to be used. If the local team cannot take that deck to their internal stakeholders, finance, legal, supply chain and use it to answer every technical objection, the deck is useless. It does not matter how high the resolution of the photography is if the margin of error on page 42 is not defined.

Strategic reframing requires understanding that what global leaders call “simplification,” Japanese teams call “information withholding.”

If you want to accelerate decisions in Japan, you must stop trying to inspire the local team and start trying to arm them. Your goal is to provide a “Decision Support Package” rather than a “Vision Pitch.” This does not mean you abandon your global strategy; it means you change the architecture of how that strategy is delivered. You must provide the “Reference Materials” appendix before the meeting, not after the follow-up. You must explicitly link the new strategy to existing company precedents even if those precedents are from a different era because precedent is the primary currency of risk mitigation in the Japanese system.

When you present a bold new direction without the weight of evidence, you are not being “agile.” You are creating a “Presentation Tax”, a hidden cost of time and credibility that the local team must pay by spending the next three months reverse-engineering the data you omitted just so they can get the first signature on a Ringi-sho.

The Bottom Line

Global presentations fail in Japan because they prioritize narrative momentum over documentation, leaving local teams with the liability of the decision but none of the evidence required to defend it. Until you provide the exhaustive “how,” your “why” will remain a source of strategic paralysis rather than a driver of growth.

Over to You

Where in your current Japan strategy deck is the “vision” creating a liability for your local team by failing to provide the documentation they need to safely distribute risk?